Mark McKergow PhD MBA

Dr Mark McKergow is co-director of sfwork - The Centre for Solutions Focus at Work. He is an international consultant, speaker and author. He is known for his energetic and accessible style, cutting edge ideas presented with his inimitable blend of scientific rigour and performance pizzazz. Mark's PhD in the physics of self-organisation and ordering of metal hydrides has subsequently transferred to a career in management consulting and development.

Mark is a global pioneer applying Solutions Focus ideas to organisational and personal change. He has written and edited three books and dozens of articles; his book 'The Solutions Focus: Making Coaching and Change SIMPLE' (co-authored with Paul Z Jackson) was declared one of the year's top 30 business books in the USA, and is now in nine languages. He is now developing new metaphors for leadership, notably around leader as host.

Mark is a Board Member of SFCT, a new worldwide association for SF consultants, coaches and leaders (www.asfct.org), and edits the academic journal InterAction. He is also a member of the Association for Management Education and Development (AMED) and the Association for MBAs (AMBA).

This paper examines the case for viewing conversations as emergent phenomena, and the practical consequences for complexity practitioners and others engaged in 'talking cures'. Post-structural thinking from Wittgenstein onwards is connected to the school of Solution-Focused practice, which has made explicit use of these ideas in a practical, pragmatic and effective form of psychotherapy and coaching. These fields can be connected by the idea of 'narrative emergence', which casts light on the ways in which new narratives are formed within apparently everyday conversations.

A living language is in a state far from equilibrium. It changes, it is in contact with other languages, it is abused and transformed. This does not mean that meaning is a random or arbitrary process. It means that meaning is a local phenomenon, valid in a certain frame of time and space... Above all, language is a system in which individual words do not have significance on their own. Meaning is only generated when individual words are caught in the play of the system (Cilliers 1998, p. 124)

This first international workshop on complexity and real world applications has brought together participants from a wide variety of areas and disciplines, with a wide range of views on the salient aspects of complexity. It seems to me that we have seen broadly three ways of connecting complexity with real world applications:

1. Modelling complex real world issues with agent-based models, to help decision making in unfolding real-time situations (for example routing of oil tankers or taxis - as seen in the work of George Rzevski (see for example Glaschenko et al (2009)).

2. Using complexity ideas as a new way of engaging with an ever-changing world, particularly in business and organisational work (see for example the notable work of Eve Mittleton-Kelly and her group at the London School of Economics). This involves making people aware of the key terms and distinctive features of complexity. Some have referred to this as 'metaphorical complexity'.

There is, however, a third strand. This was not highlighted as such during the workshop, but has become much clearer to me in the intervening period.

3. Taking seriously the idea that the world IS a complex place (in the strict meaning of the term). How are we to act when the world is always changing and unfolding in ways which are unknowable even within our understanding of the laws of physics? The contribution of Joseph Pelrine on 'On understanding software agility - from a social complexity point of view' falls into this category, as does the present paper. This is NOT metaphorical, in my view.

In seeking to grapple with a complex world, we might start by looking at two fundamentally different types of interaction - the physical and the semantic. This distinction has been memorably made by social psychologist Rom Harré as 'molecules and meanings'.

As far as anyone knows, we are all subject to the laws of physics. People can interact physically, as in one boxer striking another with gory consequences. Likewise, an oak tree grows from an acorn using comprehensible, if amazing, mechanisms. These are both molecular interactions.

Humans and other creatures also have various levels of semantic interaction - including our language. This has a physical/molecular component - vibrations in the air or marks on a page. However, the meaning of such an interaction cannot be found by merely examining the physical components - there have to be two parties who have, by some presumably social process, learned to (mis)understand each other.

It is important not to confuse these two levels. To attempt to understand a social phenomenon at a physical level would be a muddle - like trying to find what makes traffic stop at a red light by taking the light off to the lab and examining it.

This paper is an attempt to grapple with language and conversation as an emergent phenomenon, and to see what practical conclusions might be drawn. It seeks to connect these somewhat philosophical issues with a well-established yet not widely known field of conversational practice. 'Solution-focused' work in the form of therapy, coaching, OD and many other fields is practised around the world. Its development, stemming from the Brief Family Therapy Center in Milwaukee in the mid-1980s, has been very practitioner-led. One aspect of this school is to avoid theorising about generalities - and therefore most practitioners are not explicitly aware of the connections with complexity and emergence.

This paper will set out:

Introducing ideas about complexity is always a challenge, and I have found great utility in illustrating these with Conway's Life. This might be thought of a 'a very simple complex system' - the rules of the cellular automaton can be understood in seconds, and yet the ramifications of those rules are counter-intuitive and curious. For the purposes of this paper, I will not give a detailed description of either the general characteristics of a complex system (see Cilliers 1998 for at least one good version of this), or the way in which Conway's Life works (see Poundstone, 1987, for one illuminating account).

Richardson, Cilliers and Lissack (2001) give four key properties of complex systems, which give a handy way to start thinking about our lessons from Life.

Diversity of behaviours: Complex systems display a rich diversity of qualitatively different operating regimes. This is the result of the non-linear nature of the interactions. These behaviours cannot be predicted by examination of the interactions themselves - they are said to emerge. In Life terms, this means that simply knowing the interactions between the cells - even completely - does not allow us to extrapolate upwards to the behaviour of groups of cells other than in the most trivial cases. However great the understanding of ONE cell, the future behaviour of the whole system is elusive - even if all the cells are the same!

Lesson from Life: Even total understanding of one agent/unit/person is not at all the same as knowing where the interactions can take the whole system.

Large sensitivity to initial conditions and tiny changes: Since the 1960s, mathematicians have become aware that the emerging behaviour of complex systems depends on arbitrarily small differences in the initial conditions, or known starting points, of the system. This means that tiny differences introduced, either at the start or as perturbations, will introduce unknowable effects over time. These effects may be large, small or zero. And since the original conditions are not knowable with total precision, the 'status quo' future without perturbations cannot be known accurately either. The idea of designing interventions to achieve a known result - for example the propagation of best practice across an organisation - is therefore a misleading distraction in a complex system.

Lesson from Life: Tiny changes and differences can matter a great deal. Applying the 'same' intervention cannot be relied upon to produce the same result - as indeed it cannot be precisely the 'same' intervention.

Robust self-organisation: Auyang (1999) points out that alongside this extraordinary sensitivity to tiny perturbations comes a broad robustness to large disturbances. While the future of a complex system cannot be known with certainty, it is usually recognisable as being the same 'sort' of system as before. This is down to self-organisation - the agents interact to adapt to the disturbance and find some way of continuing their interaction. As large numbers of agents are involved, such systems are capable of exploring very large 'possibility spaces' and allowing the viable futures to emerge.

Lesson from Life: The future is unknowable, but recognisable. There is no chance of the dots in Life all turning into pieces of cheese.

Incompressibility: Complex systems are incompressible (see for example Cilliers, 1998), so that it is impossible to have a complete account of the system which is less complex than the system itself without losing some of its aspects. And, as tiny changes can perturb the systems in unknowably large ways, no description (either mathematical or linguistic) can offer a complete look at the system. This is 'probably the single most important aspect of complex systems when considering the development of any analytical methodology, or epistemology, for coping with such systems' (Richardson, Cilliers and Lissack, 2007 p 27).

Lesson from Life: Any model or description of a complex system must, at some level, be inadequate, and the inadequacy itself is not easily knowable. Alternative ways to work with complex systems should be sought.

Taking these four properties together, it can be said that complex systems display emergence; they develop over time in unknowable yet robust ways, and show properties which cannot be predicted, or even modelled, from knowledge of the the individual agents and their interactions. Indeed, Conway's 'Game of Life' shows remarkably that even complete knowledge of the position of each agent, and complete knowledge of all the interactional rules, fails to lead to the ability to predict the system behaviour in advance. The system is mathematically 'NP hard' (non-deterministic polynomial-time hard) (see for example Barrow 1998 for a non-technical account).

Broadly speaking, such systems have more possible futures than it is possible to assess mathematically, and so the actual future state of the system cannot be determined in advance. This is very distinct from quantum uncertainty as defined by Heisenberg in his famous Uncertainty Principle. Complex uncertainty is not a result of an inability to measure the state of the system accurately (the position and momentum of an electron, in Heisenberg's case), but of the lack of a computational approach to sort through the vast number of possible futures of the system to decide which will pertain.

The concept of emergence is not new, of course, and has roots and threads from the ancient philosophy of Aristotle and John Stuart Mill (1843) amongst many others. However, the broad conclusions about ways to deal with complex, incompressible and emergent systems seem to have gone un-noticed by both the general academic community and even by generations of 'complexity researchers' (mainly mathematicians) investigating the 'properties' of complex systems within the safe boundaries of their computers. There are of course exceptions to this, see for example Clayton and Davies (2006). I hope to lay out an overall view of the consequences of incompressibility and emergence for the investigation of social systems here.

We can examine conversation through George Rzevski's criteria for complexity (as given in his paper here).

It may even be that emergence is the most 'honest' description of the development and evolution of families, organizations and so on. Conversation and discourse, apart from a few exceptional cases such as ritual, are surely emergent - in terms of one utterance being a response to the totality of previous utterances rather than being governed by some overarching structure.

Let us examine a simple conversation and see how it relates to emergence. This is a very simple conversation between two people.

Turn 1 "Hello Eileen!" (has lots of possible grammatical responses, from which the other participant picks one)

Turn 2 "Good afternoon Mark, how are you?" (which has lots of possible responses from which the first participant picks one)

Turn 3 "Fine thanks. Have you seen Kurt lately?" (which has lots of possible responses, etc etc).

Notice that each turn is taken in the context of the previous turns, so a whole set of possible futures is present at each step, some of which are cut off by the choice of the next turn. However, new possibilities also enter at each turn.

'Conversation' here includes all the non-verbal gestures, nodding, etc. Conversations which generate new meaning are certainly emergent. These can be very everyday conversations - indeed, the potential for emergence is always present, even if not realised. To quote from Ralph Stacey (2007):

the thematic patterning of conversation is iterated over time as both repetition and potential transformation at the same time. However, this potential need not always be realized. ...Change can only emerge in fluid forms of conversation. However, it is important to understand that fluid conversation is not some pure form of polar opposition to repetition. (Stacey 2007, pp 283-284)

This being the case, it is not necessary to use such special methods as Open Space, 'deep' discussion, etc to work with complexity (though such methods may be useful - and having many conversations going at once in a group may provide useful synergy). Conversation is already emergent.

The next step is to take this idea seriously and see what it means. Let us first examine how some common conversational therapeutic and coaching practices fail to deal with the challenges of complexity.

There is a greal deal of writing and experience about people and change in the fields of psychology and psychotherapy. The latter dates from the time of Sigmund Freud in the early 20th century, and it would be surprising if this featured a complexity-friendly framework. It doesn't. (We will see later, however, how Freud's contemporary Wittgenstein comes much closer to the mark.)

Conventional psychotherapeutic work has a focus on:

This seems to me to be an example of applying thinking about 'complicated' systems - the cause of the problem must be found, requiring a highly skilled (and expensive) expert and a great deal of time. Only if the cause is dealt with can something better happen. The way of talking about emotions, as hydraulic factors which press here and burst there, is instantly understandable in the mechanics of Freud's day. Equally, the idea of diagnosis, categorising the condition as necessary information for knowing what to do about it, results from a mechanical paradigm. This is a huge simplification of a complex field into a couple of paragraphs and there are exceptions (such as Jung's work on active imagination). However, the mechanical paradigm lives on strongly today in the latest developments to the The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (relating symptoms, disorders and cures) and positive psychology.

A conclusion to be drawn here is to be very aware of the difference between stability-focused language - the pretence that things are mechanical, causal, inevitable - with progress-focused language - where smalls signs of useful change (possible and actual) are the focus.

Since the 1950s an alternative view has been put forward by therapists and systems thinkers. Starting in 1952, Gregory Bateson's research project sought to look at mental illness not as something which the patient 'had' (like the measles), but rather the results of interactions with those around them - in chief their families. Initial work in the 1960s connected with the then-current system dynamics traditions. The Mental Research Institute, Palo Alto, developed these approaches into a brief therapy method (see for example Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch, 1974). This approach was further developed by Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg of the Brief Family Therapy Center, Milwaukee during the 1980s and 1990s, moving towards an even more fluid and emergent form of practice, 'solution-focused' therapy, which I wish to highlight here. This tradition has elements in common with social construction theory (see for example Weick, 1995 or Gergen, 1999) - however, it predates or is at least concurrent with that development, and is for some reason rarely cited by social construction theorists.

Solution-focused brief therapy was initially developed by a group of therapists and academics associated with the Brief Family Therapy Center (Milwaukee, WI, USA) in the 1980's and 90's. It emerged within a practical clinical context concerned with fostering effective and efficient change in the lives of a socially diverse population of clients (Miller 1997). The precursor to the approach was a variant of strategic therapy (de Shazer 1982) and, later, it evolved into contemporary solution-focused brief therapy (de Shazer 1988, 1991). The history of solution-focused brief therapy is a process of moving from a systemic perspective to a discursive orientation emphasizing how problems and solutions are organized within clients' use of language. These changes were accompanied by evolving descriptions of observable interactional processes in therapy (Miller 1997, 2001).

A central principle of solution-focused practice is

Change is happening all the time - the simple way to change is to find useful change and amplify it.

The discursive emphases of solution-focused brief therapy became clear with the ascension of a Wittgensteinian (1958) perspective as the dominant descriptive language of the early solution-focused brief therapists (de Shazer 1988, 1991). Wittgenstein's view of the significance of language-in-use, with meaning being continually defined and redefined, draws attention away from fixed concepts of meaning. Wittgenstein is, in this author's reading, the originator of meaning as an endlessly-emerging local property - well ahead of his time, and of the later social constructionists and post-modernists.

De Shazer draws upon Wittgenstein in developing an interpretive framework for giving language to practice (Mattingly and Flemming 1994), that is, for seeing and talking about the otherwise unnoticed aspects of their interactions with clients. The therapists' interest in discourse went beyond the questions and other 'techniques' that are often associated with solution-focused brief therapy. They also included the 'philosophy' of solution-focused brief therapy, which consists of the assumptions and concerns that organize solution-focused brief therapy interactions. These are now in use in organisational change settings around the world, with a thriving international community of practitioners who have gathered at the SolWorld conferences and summer university events since 2002, and more recently a professional body, SFCT, with its own journal, InterAction (ISSN 1868-8063).

The SF approach has been shown to be effective in therapy in several randomised controlled trials and there are over eighty peer-reviewed studies in various contexts (see Macdonald, 2007). Interestingly, the success of the approach does not seem to depend on the diagnosis of the client, nor on their class or culture. This is practical evidence that the diagnose-and-categorise notion of therapy is flawed or at least unnecessary.

Since SF practice was developed in the 1990s, further connections have appeared to other fields. It is becoming a popular approach in the world of coaching and facilitation (see for example Berg and Szabo 2005). In addition there is continuing success in practical organisational settings (see for example McKergow and Clarke, 2007).

'The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook' - William James

I present the Solution Focused model here for several reasons. Firstly, it is almost unknown to complexity practitioners. Secondly, it is very well researched across many fields. Thirdly and most importantly, it offers a rare direct example of complexity in action. By taking the world and its conversations as active and emergent, huge and lasting change can be produced with very modest effort. This is in stark contrast to conventional Freudian psychotherapy, which takes many years to learn and even more (we are told) to be effective.

In their book The Solutions Focus, the present author and Paul Z Jackson defined SF practice in terms not only of simplicity but also in six SIMPLE principles. These principles are a guide to how to stay simple, by knowing what to focus on and what, in the words of William James, to overlook. Bearing in mind the difficulties of trying to clearly define a field where definitions are treated sceptically, we present them here. These principles will prepare you for the nature of SF practice in the cases that follow. The principles are:

Solutions - not problems

Inbetween - not individual

Make use of what's there - not what isn't

Possibilities from past, present and future

Language - clear, not complicated

Every case is different - beware ill-fitting theory

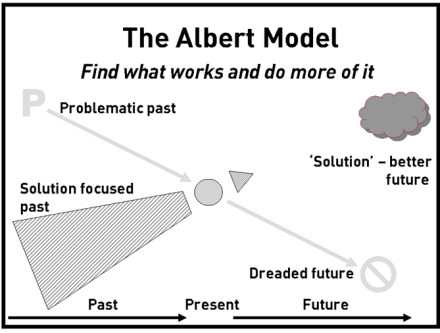

In a field calling itself Solutions Focus this may seem obvious. However, this principle is often misunderstood. The 'solution' here is not something to do next (though that will emerge) but what is wanted. This is made clear in our Albert Model (named after Albert Einstein and his famous quotation 'Things should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler').

At the heart of the SF approach is this distinction between narratives relating to the problem - ie what's wrong - and the solution - ie what's wanted. Most approaches to change seek to discover what to do next by examining the problem and seeking to address is. This works well for broken motor cars and washing machines, but less well for people and organisations. The insight of SF is that these two narratives are not related. Take five people with the same 'problem', ask them about signs that things are improving and you get five different answers. There is much more relevant information in the details of what's wanted than in the story of what's wrong.

At the same time, there is a (sometimes thin and ignored) narrative of elements or enablers of the 'solution' which have happened in the past, and may well be continuing to happen in the present. SF practitioners start to connect up these elements and look for small steps to build on what is working. The small steps, often taken as some kind of experiment, start to move things forwards and give even more information about what helps in this case. Then what works can be used and built on with even more confidence and so on.

Bear in mind that statements of 'what's wanted' and so on are formed as part of emergent conversations, are subject to change over time - they are emergent themselves. This is therefore not a 'goal' in the usual sense. A goal is something we set today to be achieved at some date in the future - and we are then judged by whether we meet it. Taking the more fluid complex lens, a goal may well make sense today and then make different sense tomorrow. This is not normal business thinking - goals must be achieved! It is the formation of these narratives through complex self-referential processes that makes this such a relevant field for the present context. The field of Appreciative Inquiry (see for example Cooperrider and Whitney, 2005) has arrived at somewhat similar conclusions, though via a different route.

Looking through this lens of emergent conversations, the idea of goals and targets seems to become problematic.

In the cases that follow you will find many examples and methods of this shift from looking at the problem axis to the solution axis. It can take skill and patience. However, the advantage of leaving the problem and its diagnosis behind are considerable, both in terms of motivation and time.

This is the most conceptual of the six SIMPLE principles. A key element of SF practice is the Interactional View, originally deriving from the work of Gregory Bateson's research project into communications which developed into family therapy and then brief therapy in the 1960s. Following the development of the simpler SFBT, Steve de Shazer drew connections with the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose later work forms a basis for post-structural linguistics. We are continuing to develop these connections today, including connections with discursive psychology and the science of emergence.

Conventional wisdom has it that individual behaviour is driven from within - by values, beliefs, motivations and many more. The 'inbetween' view is that trying to explain behaviour by reference to internal states is misleading. In practice people develop their faculties interacting with others, and so learn to speak and act during conversations. Even when they are thinking 'alone', they are doing so in the context of their prior interactional experience.

The practical upshot of this is to greatly enhance simplicity. Just don't use 'mentalistic' language about beliefs, values and so on. Instead, keep it simple by using interactional language relating to observable signs and activity. During the cases you will find many references to 'signs that things are better' or 'what would be the first sign your colleagues noticed'. These are examples of questions to prompt interactional language.

Why is this a good idea? Because the findings from research into the effectiveness of SF practice shows results that are as good or better than other approaches, in less time. It therefore seems the case that such mentalistic language is not necessary to produce change. Rather, it seems to be connected with mechanical/causal thinking. Indeed, it may be serving to muddle the issue and delay change. This is another example of the benefit of taking simplicity seriously.

SF is about finding what works in a particular given context. Therefore, anything that seems to be connected with things working, going better or even going less badly that normal may be worth utilising. This includes personal strengths, positive qualities, skills and co-operation as well as examples of the 'solution' happening already.

This may seem obvious. However, it's quite different to the commonly used idea of 'gap analysis', where the differences between the present and the desired future are the most important aspects. It's not unusual to find managers who quickly nod towards what's already going well before getting onto the allegedly more relevant topic of what is not. This is not to say that organisations should not be aware of these differences. It's simply that the building blocks for change are much more likely to come from what's already going well. You will find the practical application of this principle in every case in the book.

A sense of future possibility, of hope and optimism and positive expectations, is of course vital in any change effort. Where there is no hope, things are very difficult. The idea of possibilities in the past, however, is perhaps a more novel idea. Some think that the past has happened, is gone, is immutable. We take a different view. The past is a useful source of stories of success, examples of resources in action, even tales of adversity overcome.

The key to bringing these stories into the present, where they can influence the future, lies in identifying and drawing out their connections with the 'solution' - what's wanted. It is much easier in practice to identify relevant examples if you have some idea what you are looking for.

The idea of possibilities is also different from certainties. As soon as you become certain of what's going to happen, or indeed what happened in the past, it's much harder to start to identify the alternative possibilities. In some cases people use explanations of the past to create a firm (and unhelpful) view of the future. In SF practice we tend to steer away from explanations towards experiments and a sense of 'seeking to find what works' - particularly if the explanation is about why the problem happens and is difficult to change.

One of the working principles of SF is the idea that '$5 words may be worth more than $5000 words'. $5000 words are usually long, complicated and abstract, and sound very impressive. They are often used in explanation, theorising and academia. $5 words, on the other hand, are short, concrete and detailed. They may not sound very impressive. They are, however, usually more connected to action, movement and everyday life.

In the cases described here, you will find many examples of people gently seeking to simplify the language being used. The focus will be on the language used by the people involved in going about their everyday business, rather than on abstract and generalising language imposed by observers. This turns out to a surprisingly practical idea - it not only shows respect to those involved by taking their words seriously, it is also a good way to avoid getting into dubious explanations and generalisations.

Most approaches to organisational change seek to simplify the messy everyday world by establishing some classification scheme. If the issue is of type X, then action A is advised. This is also true of science, medicine and many other fields, and has served humanity very well.

SF works in a different way. Simply approach each case with a completely clean and open mind, seek to identify what the people want and what works. If you 'know' what should work, then you will undoubtedly try to find it and will therefore miss important clues. Not knowing what should be done is the easiest way to see clearly. In the words of Zen writer Shunryu Suzuki, 'In the mind of the expert, there are few possibilities. In the mind of the beginner there are many.' So it may be more helpful to have the mind of the beginner than the mind of the expert.

Of course there are many occasions when theories may be helpful. In these cases, we urge people to go on using them. When pre-conceived ideas are failing to fit your experience, however, you may find it helpful to let go of the idea and examine your experience again with fresh eyes.

Richardson, Cilliers and Lissack (2001) examine the challenges posed by the 'inbetween' nature of complexity. Stacey (2007) discusses the difference between conversations which remain trapped in reproducing the same patterns of talk, and those which may foster the emergence of new knowledge.

We saw earlier that no special kind of language is necessary for the emergence of new knowledge. Rather, the fluidity, spontaneity, and 'good enough holding of anxiety' of the conversational interaction itself (Stacey 2007 p 285) seem important in encouraging potentially transforming themes. The deliberate utilization of the clients' everyday language in solution-focused brief therapy and the conversational focus on small details show how this emergence of knowledge is encouraged without every referring to it in such terms.

Solution-focused brief therapists' interest in initiating change through small and often provisional steps is also consistent with complexity theorists' appreciation of modest depictions of social realities (Cilliers 2005). Modest proposals (made in the knowledge of an incomplete and uncertain context) acknowledge and accept the limitations of our understandings of and control over the complex processes of life - in stark contrast to the booming certainty of many organisational change frameworks. They also orient to the unpredictability and transformative potential that are built into complex interactional processes. McKergow and Korman (2009) explain that the interactional emergence of modest proposals in solution-focused brief therapy occurs 'inbetween' - neither inside (stemming from inner drivers, urges, motivations or other mentalistic explanatory mechanisms) nor outside (determined by external systems, narratives or other mechanisms). There are also links to the 'second cognitive revolution' of discursive psychology (see for example Harré, 1995, Potter and Wetherall, 1987).

The phrase 'narrative emergence' has been coined by Miller and McKergow (2010) as a way to summarise what we have been discussing here. We use this term to call attention to several interrelated aspects of solution-focused brief therapy as a distinctive form of discursive therapy and complex systems. The concerns include recognition that while the future is unknowable, it is an ever present possibility in the present. We continuously create and discover the future by engaging in self-organizing activities (particularly social interactions) that are, at least partly, improvised, and potentially transformative. Thus, the narratives emergent in our everyday lives are always under construction. They exist in our ongoing 'work' to make sense of and manage the exigencies of life.

What helps these narratives to emerge is somewhat beyond the scope of this paper. Some initial guidelines might include:

When narratives emerge which connect possible better futures or better lives with 'evidence' from the past (stories, experiences, observations from others, etc), lasting and meaningful change results with astounding frequency. Research from SF therapy shows a success rate of 60%-80% within a few sessions, across a wide range of diagnoses, age ranges and social class.

I propose that SF practice has important lessons for complexity practitioners, This form of practice has important parallels with the work of Wittgenstein (1958), the first post-structural thinker and linguist, and shows one way of thinking about, and participating in, conversations leading to useful and sustainable change. In so doing it challenges many tacit assumptions about therapy (McKergow and Korman, 2009).

I would like to point to three aspects of language and complex systems here, which may be relevant in applications of complexity in the real world:

1. The difference between stability-focused language (explanations, reasons, causes) and progress focused language (signs of change in both future and past). Experience in SF practice shows that focus on the latter seems to be a good way to get away from causal thinking and into something more useful.

2. The difference between internal mentalistic language (beliefs, thoughts, feelings) and interactional language (descriptions of ongoing everyday life from a variety of perspectives). The former echo Freud in terms of hydraulic causes of behaviour, the latter are about rooting change in our everyday lived experience.

3. The difference between goals (targets set in the future) and small steps (things to do quickly to move in a desired and defined direction. This may be the single most important conclusion for progress in a complex world. If things are ever-shifting, then what's clear today may not be so clear tomorrow. Focus on small steps, to be done quickly in order to find out more about what works (rather than in the expectation that everything will be instantly resolved) seems to give people a sense of control and purpose in a confusing and muddled world. There is a clear parallel here with the 'agile' school discussed by Pelrine (2010).

Auyang, S. Y. (1999). Foundations of Complex-System Theories in Economics, Evolutionary Biology, and Statistical Physics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press ISBN 9780521778268

Barrow, J.D. (1998), Impossibility: The Limits of Science and the Science of Limits, Oxford UK: Oxford Univerity Press ISBN 9780195130829

Berg, I. K. and Szabo, P. (2005). Brief Coaching for Lasting Solutions. (New York: WW Norton) ISBN 0393704726

Cilliers, P. (1998). Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems. (London, Routledge) ISBN 978-0415152877

Cilliers, P. (2005). Complexity, Deconstruction and Relativism. Theory, Culture & Society, 22, ISSN 0263-2764 255-267

Clayton, P. & Davies, P. (2006). The re-emergence of emergence. (Oxford: Oxford University Press) ISBN 9780199287147

Cooperrider, D. and Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change. (San Francisco:Berrett-Koehler) ISBN 9781576753569

De Shazer, S., Dolan, Y., Korman, H., Trepper, T., McCollum, E., & Berg, I.K. (2007). More Than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution Focused Brief Therapy. (Binghamton NY: The Haworth Press) ISBN 978-0789033987

Glaschenko, A., Ivaschenko, A., Rzevski, G., Skobelev, P. "Multi-Agent Real Time Scheduling System for Taxi Companies". Proc. of 8th Int. Conf. on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (AAMAS 2009), Decker, Sichman, Sierra, and Castelfranchi (eds.), May, 10-15, 2009, Budapest, Hungary. (downloaded from http://www.rzevski.net/09%20Scheduler%20for%20Taxis.pdf)

Gergen, K. (1999). An invitation to social construction. (London: Sage Publications) ISBN 9780803983779

Harré, R. (1995). Discursve Psychology, in Jonathan A Smith, Rom Harré and Luk van Langenhove (Eds.) Rethinking Psychology, (London: Sage Publications) ISBN 9780803977358

Jackson, P. Z. and McKergow, M. (2007). The Solutions Focus: Making coaching & change SIMPLE. (London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing (second edition) ISBN 978-1904838067

Macdonald, A. (2007). Solution-focused Therapy: Theory, Research and Practice. (London: Sage) ISBN 978-1412931175

Mattingly, C. and Flemming, M. H. (1994). Clinical Reasoning: Forms of Inquiry in a Therapeutic Practice. (Philadelphia, F.A. Davis Company) ISBN 978-0803659377

McKergow. M. and Clarke, J. (2007). Solutions Focus Working: 80 real-life lessons for successful organisational change. Cheltenham: SolutionsBooks ISBN 978-0954974947

McKergow, M. and Korman, H. (2009). Inbetween-Neither Inside Nor Outside: The Radical Simplicity of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy. Journal of Systemic Therapies (JSSN 1195-4396), 28, 2, 39-49

Miller, G. (1997). Becoming Miracle Workers: Language and Meaning in Brief Therapy. (New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction Publishers) ISBN 978-0202305714

Miller, G. (2001). Changing the Subject: Self-Construction in Brief Therapy. in J.F. Gubrium and J.A. Holstein (ed.) Institutional Selves: Troubled Identities in a Postmodern World pp.64-83, (New York, Oxford University Press) ISBN 978-0195129274

Miller, G. and McKergow, M. (2010). From Wittgenstein, Complexity, and Narrative Emergence: Discourse and Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (in A. Lock and T. Strong, Discursive Perspectives in Therapeutic Practice. (Oxford: Oxford University Press) to be published)

Potter, J., & Wetherall, M. (1987). Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour (London: Sage) ISBN 978-0803980563

Poundstone, W. (1984). The Recursive Universe: Cosmic Complexity and the Limits of Scientific Knowledge. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0688039752

Richardson, K. A., Cilliers, P. and Lissack, M. (2001). Complexity Science: A "Gray" Science for the "Stuff in Between" Emergence (ISSN 1521-3250), 3, 6-18

Stacey, R. (2007). Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics: The Challenge of Complexity. 5th edition. (London: Prentice-Hall) ISBN 978-0273708117

de Shazer, S. (1982). Patterns of Brief Family Therapy: An Ecosystemic Approach. (New York, The Guilford Press) ISBN 978-0898620382

de Shazer, S. (1988). Clues: Investigating Solutions in Brief Therapy. (New York, W.W. Norton & Company) ISBN 978-0393700541

de Shazer, S. (1991). Putting Difference to Work. (New York, W.W. Norton & Company) ISBN 978-0393334708

Watzlawick, P., Weakland, J. and Fisch, R. (1974). Change: Problem formation and problem resolution. New York: WW Norton ISBN 978-0393011043

Weick, K. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. (London: Sage Publications) ISBN 9780803971776

Wittgenstein, L. (1958). Philosophical Investigations. (New York, Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.) ISBN 978-0631146704

838 days ago

1125 days ago

1247 days ago